Pathology of the Oppressed

(Title is a play on the title of the classic book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by Paulo Freire)

Lessons from neglected houseplants

Like many ADHD millennials, I have committed crimes of neglect against houseplants. I have proven the helpful people at Lowe’s garden center wrong, as it turns out I can in fact kill the plant that “anyone can take care of.” My second money tree sits forlorn in the corner of my office, leaves brown from underwatering (or maybe overwatering?) and jagged from being munched on by my cat. I have no idea if it’s getting the right amount of light. Someone once told me I needed to spray it with mist twice a day. I have not done that. I really should figure out how to revive it and help it thrive. I will probably forget to do that.

In my years studying human wellbeing, I have asked the question I should be asking on behalf of my plants: Under what conditions do we thrive? I’ve joked to clients that humans are just complicated house plants; give us the right environment and conditions, and we’ll do just fine. But after a few years observing that the folks who make the most progress in counseling are the ones with the most resources and support (we call these protective factors), I don’t see that as a joke anymore. Humans, like all lifeforms, thrive under certain conditions and languish under others. Take us out of the social, geographic, climate, and nutritional conditions we’re meant for, and we fall apart. That joke was only funny when part of me believed that mental health had more to do with the individual than the environment.

Many practitioners in the field of mental health ignore the importance of environment and assign blame to the person who is suffering. If someone is failing to thrive and showing consistent signs of distress, we call that distress pathological and assign a diagnosis to the individual, implying that something is wrong with them, or that they aren’t adapting to the environment in the right way. We then give them a treatment plan aimed only at changing internal variables (such as coping skills, cognitive distortions, and self-image, to name a few) through medication or intervention, then call lack of progress “treatment resistance.” It is only the multiculturally informed, systems-thinking, and likely heterodoxic therapist who can acknowledge the role of the environments and systems that an individual is nestled in. Going back to the houseplant analogy: we seem to think that the neglected houseplant is the one that needs to change, not the incompetent caretaker.

Before going on, let me clarify that there are many people who are helped by the conventional model of mental health (commonly referred to as the medical model). Millions of hours of research and clinical practice have not all been for naught. I have personally seen folks improve their quality of life thanks to therapies like CBT, DBT, and EMDR. My suggestion isn’t that these things are unhelpful, it’s that treatments aimed only at altering individuals don’t address the bigger picture. And, maybe, we shouldn’t have to work so hard to inoculate folks against the society they live in.

Maybe if at least 22.8% of the fish in the pond are sick, something is wrong with the pond.

Pathologizing the victim

Starting from the bottom

Imagine that I took my neglected money tree to a plant specialist to improve its condition. Once a week, the specialist tried to improve the tree’s ability to tolerate neglect. Over time, it might get a little bit better at enduring its sorry conditions, but it would be foolish to expect it to ever thrive again. Despite what improvements we can make in the tree’s tolerance, we would be fighting its genetics, its built-in responses to the environment. We would be attempting to force this organism to thrive in an environment that it is not designed to thrive in. Seems like a fool’s errand. A competent plant specialist would evaluate the tree, turn to me, and say plainly: “Dude. Water your tree.”

Those who are following this analogy may reply: But humans aren’t houseplants! We are more complex; we have will, agency, and the ability to change our circumstances. We are not bound to our environments!

I agree! And we can use these qualities to help us find creative solutions to problems, even if our environment isn’t ideal.

But not every human has equal access to these qualities. Developmental trauma is a widespread reality that means many folks are developmentally disadvantaged because of the conditions they grew up in. They did not get the opportunity to develop resilience to stress, executive function, cognitive skills, self-soothing, or reliable motivation. In many cases, stress due to factors beyond their control trapped them in narrow cycles of behavior and thinking entirely focused on managing trauma. As a result, they have many overwhelming obstacles to “pulling themselves up by their bootstraps.”

What if my money tree had been raised in nutrient deficient soil with inadequate light before I even bought it? It almost certainly wouldn’t have been able to withstand the poor conditions of my neglect.

A common picture of suffering

To ground this in real human experience, let’s examine the life of an individual who suffered from developmental trauma. I’ve put together this hypothetical person using the most common identities, life experiences, and ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) I see in my counseling practice. It’s a common profile of folks who seek mental health services, sadly:

Glen is a 24 year old, cishet, black/white mixed-race man who grew up in a low income, working class family like most Americans. Glen’s parents both worked, and he was raised largely by the television and video game console in the company of his older siblings. By age 13, Glen was suffering from depression and anxiety, but he was not able to get help. His parents, who were exhausted from raising children and working, often punished Glen for his perceived misbehavior, such as being quiet, withdrawn, and irresponsible. His father binge drank at least once a week and would become angry and yell at his children while drunk. Glen became emotionally distanced from his family and instead connected with a few friends from school who mostly socialized online and through video games. He took up smoking marijuana at age 16 and continued into adulthood. Because Glen did not have financial assistance or guidance from adults who could navigate the educational system, Glen did not attend college and ended up working various low-paying jobs with little to no upward mobility, despite having dreams of working in digital art for television and video games. At age 24, Glen seeks mental health services and is diagnosed with depression and cannabis use disorder. He is prescribed an antidepressant and given psychotherapy. Like over half of folks in treatment for depression, he does not respond to psychotherapy. Soon, he drops out of treatment. Glen keeps taking his medication, noting a small improvement in mood, but he still doesn’t feel fulfilled. In Glen’s clinical notes, Glen is classified as “treatment resistant,” as he “is unwilling to follow through on the treatment plan.”

Viewed through the medical model of mental health, Glen’s depression and habitual cannabis use are illnesses that have an etiology and a cure. On the surface, this is not offensive. For those of us who struggle with depression and addiction, it makes sense to frame these as diseases. Like most diseases, they cause great suffering, and life would be better without them. (Though some argue that diagnosis itself is harmful).

But what happens to the most important question of all: “what do we do about these issues?” if we only identify the roots of mental illness in the individual? What happens to the spirit of the suffering person when they are implicitly told (or maybe explicitly, in some cases) that they alone are to blame for their suffering? What happens when our efforts convey to them: “Sorry the world you live in sucks, best we can do is help you try to tolerate it.”

An ecological model of mental health

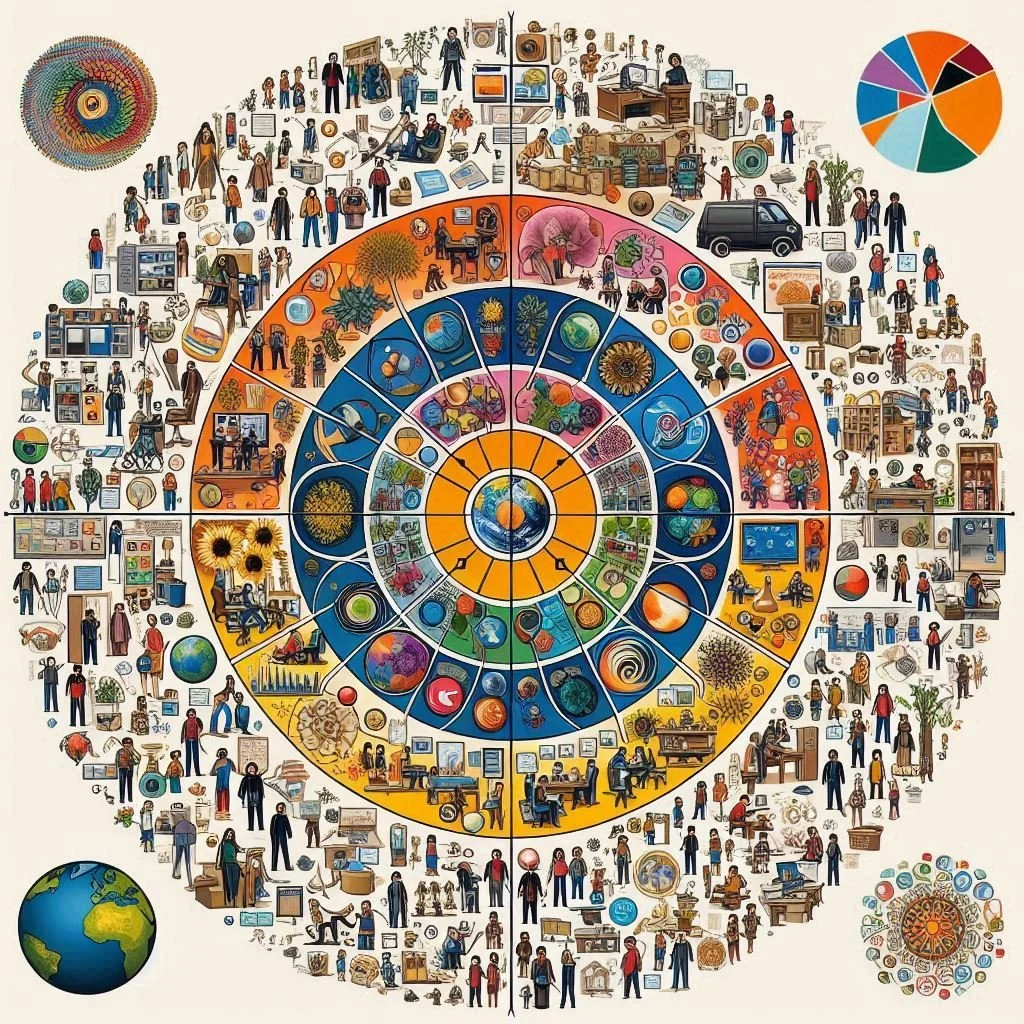

Popular ecological models of human wellbeing (Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory is the inspiration for this diagram) map out the intersecting systems that humans are a part of. If we are married to the medical model of mental illness, then we may be tempted to attend only to the red circle in the middle of the diagram, which accounts for the individual and their biology, genetics, and psychological features. A systems-oriented practitioner may also incorporate knowledge of the social relationships and understand their suffering in that context. But what about the greater systems that define an individual’s life? What about the most fundamental, organizing principles of the world they live in: the rules, laws, policies, ideas, values, and beliefs that form the greater world? And, perhaps most important of all: what about the people and institutions that hold power over the individual?

Using this model, let’s explain the influences on Glen’s mental health at every level.

Individual: Glen has inherited a genetic and epigenetic propensity for PTSD, which made him vulnerable to the effects of traumatic stress. Glen also inherited personality characteristics of his mother (submissive, deferential, avoidant), which created vulnerability to depression. Glen’s nutritional circumstances in childhood made him vulnerable to type 2 diabetes and increased his insulin resistance, making him vulnerable to physiological symptoms such as lethargy. Chronic exposure to stress in adolescence further impacted Glen’s health and reduced his psychological and physiological resilience to stress.

Relationships: Glen’s family structure was authoritarian, and Glen developed protective coping styles (avoidance, people-pleasing, low-grade dissociation) in order to deal with the stress. Both of Glen’s parents dealt with the effects of trauma through avoidance, addiction, and triangulation of their children. Glen’s sense of safety in intimate relationships was interrupted by family conflict and his father’s anger, leading to avoidant attachment. As a result of his early relationships with caregivers, Glen feels alone, uncared for, and unimportant in adult relationships. The template for relationships Glen acquired in early life has prevented satisfying relationships from being formed as an adult.

Interface with systems: Glen interfaces with powerful systems primarily through work as a low-level employee of a megacorporation. Glen’s mental health is impacted by his lack of power within the organization, low wages, perceived inequality among peers, difficult working conditions, an unpredictable schedule, unfair treatment at the hands of a manager, and benefits that do not allow him to get thorough medical care without also paying out of pocket. Glen also experiences implicit racial discrimination at work, disheartening him.

Power-holding institutions: Glen’s corporation is publicly traded, and the C-level executives have compensation packages of $32 million a year, on average, which is approximately 700 times Glen’s yearly salary. A handful of majority shareholders and executive leaders are responsible for all the decisions that affect Glen’s income, benefits, and working conditions. Glen’s company has been evaluated by third party labor investigators as abusive to workers and hostile towards unions. Multiple labor laws are violated at his worksite, but fear of corporate retaliation prevents violations from being reported, and the state government has moved towards siding with corporations in these disputes. Glen votes in state and local elections but is in the minority party. The party in charge of state government ran on the platform of ending DEI programs, which includes scholarships that would have helped Glen and other students of color attend college.

Defining trends: Glen lives in a capitalist economy characterized by wealth inequality. According to academic experts on global politics, Glen’s country shows more features of oligarchy and plutocracy than representative democracy. Both economically and politically, the trend is that the interests of elite groups (which pass down power along family lines through transfer of wealth and ownership) are disproportionately represented in law and policy. Glen’s country has an informal economic class system that privileges certain racial groups (wealth and power have remained in the hands of white people and have transferred to other racial groups at rates inconsistent with population changes). In this class system, Glen and his family are lower-class (or working-class), which means they have less than 1/33th the wealth of the average upper-class family. At the highest levels of the class divide, 1% of families own 30% of the total wealth in the country, and 0.1% owns 14%. Glen’s community is predominantly white and is located in an area of the country that historically enslaved, abused, and exploited Glen’s ancestors. The legacy of this history remains in the failure to transfer stolen wealth to Glen’s family, implicit and unacknowledged negative attitudes towards people with Glen’s skin color, and a growing political movement that enables and justifies explicit racism.

Ideological era: Glen’s country and state have historically endorsed economic policies that come from ideas such as neoliberalism, market fundamentalism, and capitalism. The philosophical pillars of many political and economic systems have their roots in assumptions about human nature that were taken from early work in evolutionary psychology: that humans’ animal instincts for dominance, resource hoarding, and competition are primary, and that economic systems must allow for these impulses to play out. Ideas such as meritocracy, Manifest Destiny, white supremacy, American exceptionalism, eugenics, and being chosen by god have all served to rationalized the unequal distribution of resources and power and justify the ruling class.

What is the healthy emotional reaction to abuse, exploitation, and injustice?

To apply this model to Glen’s lived experience, let’s work backwards from the largest system Glen is a part of, showing how the features of that system contribute to Glen’s depression.

Ideological era: In a system that advocates for meritocracy and implicit (and increasingly explicit) white supremacy, Glen receives the message that he is inferior (not white) and not good enough (not wealthy). These core messages are conveyed to Glen in the skewed allocation of resources to whites, negative treatment and attitudes based on his skin color, in implicit comments from others, and in the implicit messages in media that wealth is evidence of worthiness and value. These core messages contribute to Glen’s depression, as feeling inferior and not good enough contribute to feelings of hopelessness and rejection.

Defining trends: The immense wealth gap between Glen and the ruling class is inherently disheartening. Glen often feels anger and shame when he encounters signals of wealth and power, especially in the hands of white families who passed on wealth intergenerationally. Glen does not have the time to process these feelings, because they are so overwhelming, and because he has to spend so much of his energy on “earning a living” (a common phrase which indicates that, deep in our shared belief structure, we believe that a person must earn the right to live). The combination of anger, shame, feeling disheartened, and being primarily occupied with survival greatly contributes to Glen’s depression. Besides the plain consequence of not having energy at the end of the day to enjoy anything besides low-energy hobbies, Glen cannot even fathom how he might overcome the oppressive feelings of anger and shame that are so often in the background. Glen does not see any members of his (fractured) community that have modeled working with these feelings.

Power-holding institutions: The owners and decision-makers of Glen’s company are the gatekeepers of some of the most meaningful variables in Glen’s wellbeing. Though they could massively improve his quality of life (increase his pay, increase the quality of his healthcare, increase the quality of his working conditions, etc.), they choose not to in order to increase profits for themselves and shareholders. Glen correctly feels anger about this injustice, but is once again given no recourse for this, given the lack of power and agency he has. The feelings of powerlessness and unfairness increase his sense of hopelessness, which contributes to his depression.

Interface with systems: Glen experiences lack of power and agency in the company he works for. His managers, their bosses, and their bosses are able to exert control over Glen’s life by manipulating his work schedule, his income, his healthcare, his social setting, and his expressed identities and after-work activities. They do so as they see fit, in order to increase the value they gain from Glen’s work. Glen suffers for the lack of agency in his work, as he feels overworked, underpaid, underappreciated, and unable to affect change in his favor. This greatly contributes to his depression, as he feels powerless over his situation.

Relationships: Glen’s authoritarian family led to depression and anxiety in Glen through a number of ways, not limited to feeling powerless and unimportant in his own family. The relationship template that Glen acquired through this upbringing (“I must avoid people to be safe, and if I am close with someone, I must be hypervigilant about their needs in order to keep them from attacking me”) led to unsatisfying adult relationships and an inhibited ability to form community, leading to further feelings of depression.

Individual: Glen’s genetic and epigenetic inheritance for vulnerability to traumatic stress and depression led to him experiencing chronic overwhelm and depression, given the environmental stressors he faced throughout his life. Because of this, developmental opportunities were missed (resources were spent managing distress rather than developing), and Glen does not have the executive function, tolerance for distress, relational skills, or cognitive flexibility that would grant him strength and adaptability in his situation. Glen feels hopeless due to the sense that he cannot overcome any of his personal challenges, which contributes to his chronic depression.

When we look at Glen’s depression through this lens, we see that powerful forces well beyond Glen’s sphere of influence are contributing factors. While Glen could be helped by a therapist with a good grasp on developmental trauma, how much easier would his recovery be if his environment was not so hostile towards him? How much better would therapeutic outcomes be if our economy and powerholders did not inflict so much unnecessary suffering on the disadvantaged?

Rethinking therapy

In light of this analysis, therapy focused only on the individual is woefully insufficient. Like the plant specialist who tried to make an unfortunate money tree better at enduring neglect, therapists who frame suffering and distress only in terms of the individual are missing the forest for the trees. How do we improve mental health care, then?

Reclaiming what has been taken

First, we need to change some basic shared practices. Therapists should be mindful to not endorse or normalize exploitation in their practices. This looks like:

Identifying exploitation and injustice in clients’ systems

Normalizing negative reactions to exploitation and injustice

Empowering clients to access and process sadness, grief, and anger at being exploited

Helping clients to find community that honors their experience and rights

Speaking out against practices and treatment decisions that ask clients to repress, rationalize, and disregard their negative reactions to exploitation and injustice

Reading and integrating essential lessons from systems-based models of mental health, such as liberation psychology

Next, we need to reshape the culture and structure of mental health organizations. This could look like:

Working with wider communities, rather than just the individual

Viewing mental health as an integrative model that incorporates all systems outside the individual

Incorporating justice work and advocacy into the mission of mental health organizations

Working in a collaborative model that incorporates community, group support, and essential resources into the treatment plan

Partnering with justice organizations, labor unions, and other organizations that can help clients get support for system-level issues

Modeling economic justice in our organizations by eliminating massive pay discrepancies, having collaboratively owned practices, and eliminating barriers to entry for disadvantaged prospective practitioners

This is just a start. Therapists, technicians, supervisors, and power-holders within the mental health field must take it upon themselves to organize and create grassroots change. This is not a matter of mere political ideology; it is imperative for the well-being of our clients. If we continue to treat suffering as the problem of unrelated individuals, we will allow systems to keep churning out more suffering. Rather then resolving suffering after the fact, let’s prevent it from happening. Rather than working uphill to make people tolerant of neglect and abuse, let’s return them to the environments they were made to thrive in.